Ebola and the eye

Related content

Survivors of Ebola virus infection may present late with a spectrum of ocular manifestations, ranging from mild retinal scarring to complete bilateral blindness resulting from tractional retinal detachment, cataract and glaucoma secondary to intraocular inflammation.

An infectious disease specialist’s brush with death during the 2014 Ebola crisis in West Africa proved instructive to ophthalmologists.1 On becoming severely ill with signs of having contracted Ebola virus disease (EVD), the doctor was evacuated to an isolation facility in the United States for supportive care, where he eventually recovered. A few weeks later, he noticed blurring of vision, pain and redness in one eye, and was diagnosed with uveitis. An aqueous sample from the affected eye was sent for analysis, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay demonstrated the presence of replicating Ebola virus.

Ebolavirus and other viruses causing uveitis

Of the six species in the Ebolavirus (EBOV) genus, four infect humans, causing an acute haemorrhagic fever that is associated with very high case fatality. The finding of replicating Ebola virus in aqueous is not surprising: Marburg virus, a member of the same Filoviridae family (enveloped, filamentous virions with a negative sense RNA genome), had been isolated from the intraocular fluid of infected persons several years before.2 Moreover, in previous outbreaks, Ebola virus infection had been noted to precipitate uveitis in a minority of survivors.3 In addition, Flaviviridae such as Zika, Dengue and West Nile viruses, and Togaviridae such as Chikungunya also cause intraocular inflammation.4

Ocular complications of Ebola virus disease

Ocular complications form part of post-Ebola virus disease syndrome, which also includes symptoms of joint and muscle pain and sometimes neurological problems.

A longitudinal study in Liberia established that EVD survivors have a significantly higher incidence of uveitis than a control group of close contacts.4 Uveitis is the most common ocular complication of EVD, affecting nearly one third of people recovering from EVD.

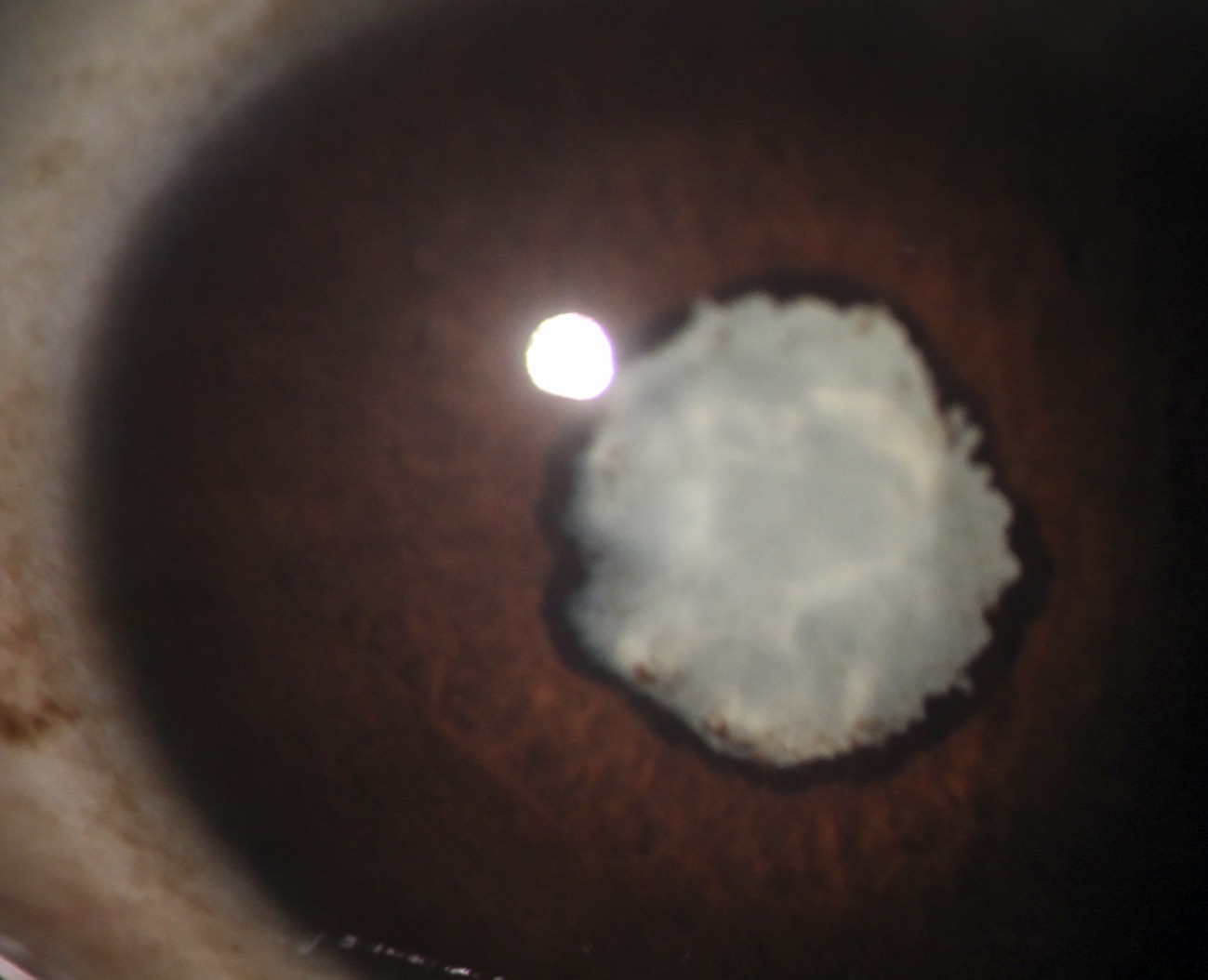

A range of signs are possible, including non-granulomatous anterior uveitis, posterior synechiae, iris atrophy, vitreous inflammation, chorioretinal scarring, panuveitis and optic neuropathy. These findings reflect direct viral invasion of the normally immune-privileged intraocular space. Inflammation can range from mild to severe, causing raised intraocular pressure, cataract (Figure 1), tractional retinal detachment and phthisis, and may affect both eyes, causing visual impairment or complete blindness.5

A variety of chorioretinal lesions may be found in survivors, such as pigmented retinal scars with a hypopigmented halo (Figure 2).6 In a study of 50 survivors, no evidence of viral persistence in the eye was found at a median of 19 months after diagnosis, indicating that cataract surgery could be undertaken safely.7,8

Management of uveitis resulting from Ebola

Treatment options include topical or systemic ocular antihypertensives, cycloplegic and mydriatic agents for analgesia and to prevent synechiae, and topical corticosteroids.

The role of antiviral drugs in eliminating intraocular infection with Ebola virus is currently being evaluated.

Implications

In those recovering from Ebola infection, the finding of treatable eye disease which can lead to visual impairment has two implications for organisations providing health care to Ebola survivors.

1. Offer follow-up eye examinations to all Ebola survivors

Health care workers should be prepared to assess the eye, which should include:

- Assessing vision

- Examining the fundus

- Measuring intraocular pressure.

Health workers can use a smartphone app to measure visual acuity, with the addition of a camera adaptor clip to visualise the fundus.9 With training, intraocular pressure can be measured using portable instruments.

2. Develop treatment and referral pathways

Adequate treatment and referral pathways should be developed, potentially using retinal images for remote consultation with an ophthalmologist.

Happily, the infectious disease specialist who developed Ebola uveitis partially recovered his vision, but others are not so lucky.

Recent Ebola outbreaks have had the unexpected effect of exposing the striking shortage of ophthalmic services available in affected communities, as well as the lack of preparedness to deal with its ophthalmic consequences. For instance, some clinicians have been reluctant to treat survivors with cataract due to unfounded fears over persisting infection. This adds to the already overwhelming burden on health services in countries struggling with the aftermath of an Ebola epidemic.

References

1 Varkey JB, Shantha JG, Crozier I, et al. Persistence of Ebola virus in ocular fluid during convalescence. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2423-2427.

2 Gear JS, Cassel GA, Gear AJ, et al. Outbreak of Marburg virus disease in Johannesburg. Br Med J. 1975;4:489–493.

3 Kibadi K, Mupapa K, Kuvula K, et al. Late Ophthalmologic Manifestations in Survivors of the 1995 Ebola Virus Epidemic in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:S13–S14

4 Merle H, Donnio A, Jean-Charles A, et al. Ocular manifestations of emerging arboviruses: Dengue fever, Chikungunya, Zika virus, West Nile virus, and yellow fever. J.Fr. Ophtalmol. 2018;41: e235–e243.

5 Prevail III Study Group. A longitudinal study of Ebola sequelae in Liberia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):924–34.

6 Yeh S, Shantha JG, Hayek B, et al. Clinical Manifestations and Pathogenesis of Uveitis in Ebola Virus Disease Survivors. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:1128–1134.

7 Steptoe PJ, Scott JT, Baxter JM, et al. Novel Retinal Lesion in Ebola Survivors, Sierra Leone, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(7):1102–1109.

8 Shantha JG, Mattia JG, Goba A, et al. Ebola Virus Persistence in Ocular Tissues and Fluids (EVICT) Study: Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction and Cataract Surgery Outcomes of Ebola Survivors in Sierra Leone. EBioMedicine. 2018;30:217–224.

9 Bastawrous A, Rono HK, Livingstone IAT, et al. Development and Validation of a Smartphone-Based Visual Acuity Test (Peek Acuity) for Clinical Practice and Community- Based Fieldwork. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(8):930–937.